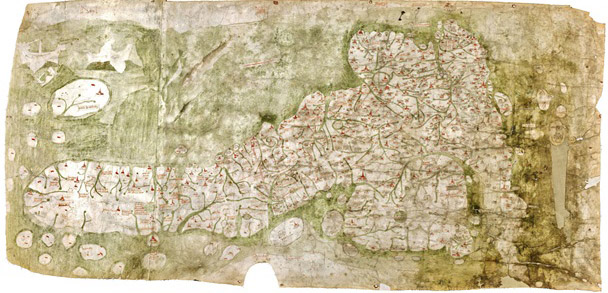

So I’ve just got back from a residency in Cornwall where I was actually able to visit Lands End!. One of the ancient sites we visited was Boscawen-ûn Stone Circle.

“The site dates from the late Neolithic-early Bronze Age (approx. 2500-1500 BC) and consists of an ellipse circle of 19 stones, ranging in height from 0.9m (3ft) to 1.4m (4.5ft). One of these stones on the NE side is made of almost pure white quartz. In addition, there is an off-centre leaning stone 2.4m (8ft) high. It is not known whether this stone was always leaning at this angle or whether it has slipped over the years. In the NE side of the circle there is a jumble of stones that may have been part of a burial cist. There is a gap between stones on the W side of the circle, similar to the Merry Maidens stone circle but on the opposite side.

Folklore and Legend

Boscawen-ûn; which is Cornish for ‘elder tree on the downs’, takes its name from the nearby farm. The circle was recorded as far back as the early medieval period in the Welsh Triads, as one of the three principal gorsedds (Bardic meeting places) of the island of Britain. In 1928, the revived Gorsedd of the Bards of Cornwall was inaugurated at the site.

Purpose and Meaning

Like the other stone circles in West Penwith, it seems likely that Boscawen-ûn was a place for ceremony and ritual. It is known that quartz was seen as a sacred stone to the megalithic builders (when the central Hurlers circle was excavated on Bodmin Moor a whole layer of quartz foundation stones were found), so the quartz stone in the circle may have had some significance relating to healing and perhaps the moon. The fact that the circle, like others in West Penwith, had 19 stones may also relate to the 18.64 year cycle of the moon, or the 19 year metonic cycle of the moon and sun. Also, the centre stone faces in the direction of the midsummer solstice sunrise, towards an outlying standing stone, and the rising sun at midsummer illuminates a carving of two axe-heads that lie towards the base of the stone. Axes were important to the Neolithic and Bronze-Age peoples as ritual objects, and Cornish greenstone axes were traded with other tribes in England and elsewhere, so this carv- ing on the centre stone is probably a sacred symbol. In the other direction, the sun can be viewed setting between the centre and quartz stones at Samhain (Oct 31st), a pre-Christian festival, when viewed from a spot on the opposite side of the circle.

Boscawen-ûn (prounounced Bosca-noon) Stone Circle lies to the south of the main A30 road between Penzance and Land’s End about a mile before Crows-an-Wra. OS grid reference SW 4122 2736.”

Text reproduced from https://cornishancientsites.com/ancient-sites/boscawen-un-stone-circle/ , image reproduced from https://www.isleofalbion.co.uk/sites/14/boscawen_un.php (accessed 22/11/23)