Abstract forms and spatial experience

The function of copying or transcription

The play between abstraction and representation,

Equivalents – Fall

Artifacts and relics.

The cast and the copy; a function of authorship and reproduction.

Participation as a function of the original

Participation as an act of design or arrangement

Participation as a challenge to authority,

Participation as a vehicle for heterogeneity

Avalanche

Or performance

Of the fragmented mark

Of the symbolic equivalent

Of play between absence and presence

Performing the failure of the mark or trace of bodily action

The Shadow [Detective]

Fingerprint

The Shadow [Detective] collecting commodities and subjects as a basis for subsequent practices.

Slumber

Reproduction as a basis for quotation and reference

Reproduction as mediation and transformation of

Perpetual Photos and Plaster Surrogates

Originals decay or deteriorate.

Mortar and Pestle

Diagrams construct an ephemeral site in place of the object

Diagrams as a form of delay

Diagrams as a form of intent:

Viewing Matters, Face to Face in the Public Toilets

‘May I Help You?’

‘Yes, I would like a bag of donuts and 3 urinals please.’

‘Not Here’

Avalanche

Lick, Lather and Gnaw at impermanence as the index

Lick, Lather and Gnaw at the contingent object

Lick, Lather and Gnaw at the experience

Lick Lather and Gnaw at the material evidence of authenticity

Gnaw at organic materials

Gnaw at chocolate, lard and soap

And yet still there looms a galvanized iron wall and a straight single tube where there dances the

Preserved Head of a Bearded Woman decorated with a String of Puppies

Puppies which need a lot of care and attention

What is this Strange Fruit [for David]?

Painted Bronze, Fountain Meltdown

The scrap metal process separates idea from material truth: an Island within an Island

No amount of Litanies can stop this Statement of Esthetic Withdrawal

The artist’s hand now becomes an object of desire along with Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals.

Drowned Monuments and Shared Fate; a function of external evidence like Every Building on the Sunset Strip

Short Circuit – Casting, Splashing, Torqued Ellipses

a simple ‘verb list’

Remade readymades,

Readymade readymades

Eureka!

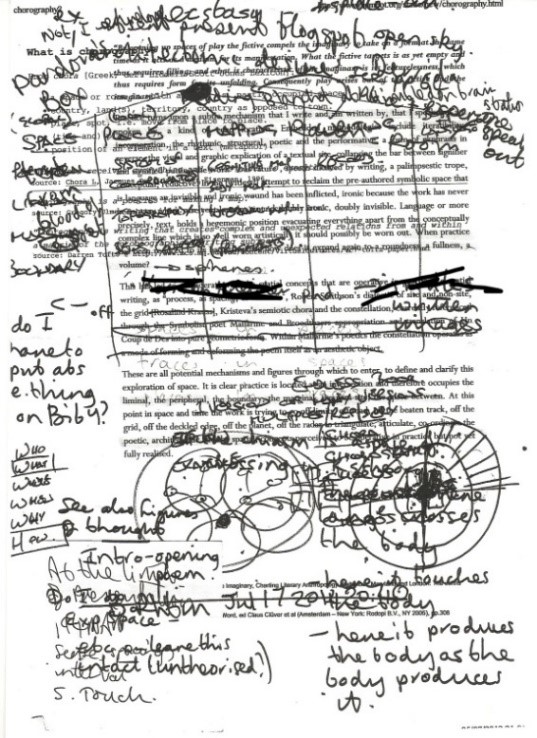

Image reproduced from https://imagejournal.org/article/gravity-and-grace/ (accessed 25/11/22)