I am in the process of preparing for my transfer exam next month which requires a report, a body of practice, a presentation and as a PGR candidate I undergo a viva. Here is the synopsis of my research as it stands presently:

The purpose of the PhD research is to explore and critically evaluate the contemporary relevance of chorography as a practice research method for the critical examination of place. The research aims to situate chorography as a significant and relatively under-acknowledged approach in visual art to map characteristics of the locale by examining the relations between the physical site, its numerous interpretations, and representations. It seeks to investigate the performative and embodied experience of chorographic practice as a potential original contribution to knowledge. Additionally, the research aims to develop new ways to examine artistic practices of place-making and its application in visual art by restoring, developing, and communicating a connection between chorography, past and present. Overall, the purpose of the PhD research is to contribute to the understanding and application of chorography in contemporary artistic practice and research, specifically focusing on its application to the site of Brontë country.

Antiquarianism

Seeing England

In the seventeenth century antiquarianism was a well-respected profession and antiquarian works were in demand, particularly amongst the gentry, who were especially interested in establishing lineage and the descent of land tenure. Although intended primarily as a source of information about who owned what and where, they often contained fascinating descriptions of the English landscape. Charles Lancaster has examined the town and county surveys of this period and selected the most interesting examples to illustrate the variety and richness of these depictions. Organised by region, he has provided detailed introductions to each excerpt. Including such writers as John Stow, William Dugdale, Elias Ashmole, Daniel Defoe, Gilbert White and Celia Fiennes, this is a book that will appeal to anyone with an interest in both national and local history and to lovers of English scenery.

Text reproduced from https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Seeing_England/6E87AwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 (accessed 14/01/24)

A Perambulation of Kent

“A Perambulation of Kent is the first English county history. It was written by William Lambarde, an Elizabethan antiquarian and lawyer. Lambarde wrote the text in 1570 but it was not printed until 1576. The book describes a journey through Kent and describes the antiquities of the county and its influence on English history. The text also includes a copy of Lambarde’s map of the ‘Heptarchy’ or the kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England that he had first included in a collection of Anglo-Saxon laws he published in 1568.”

Text reproduced from https://www.rct.uk/collection/1072284/perambulation-of-kent, image reproduced from https://www.stellabooks.com/publisher/adams-amp-dart (accessed 13/06/23)

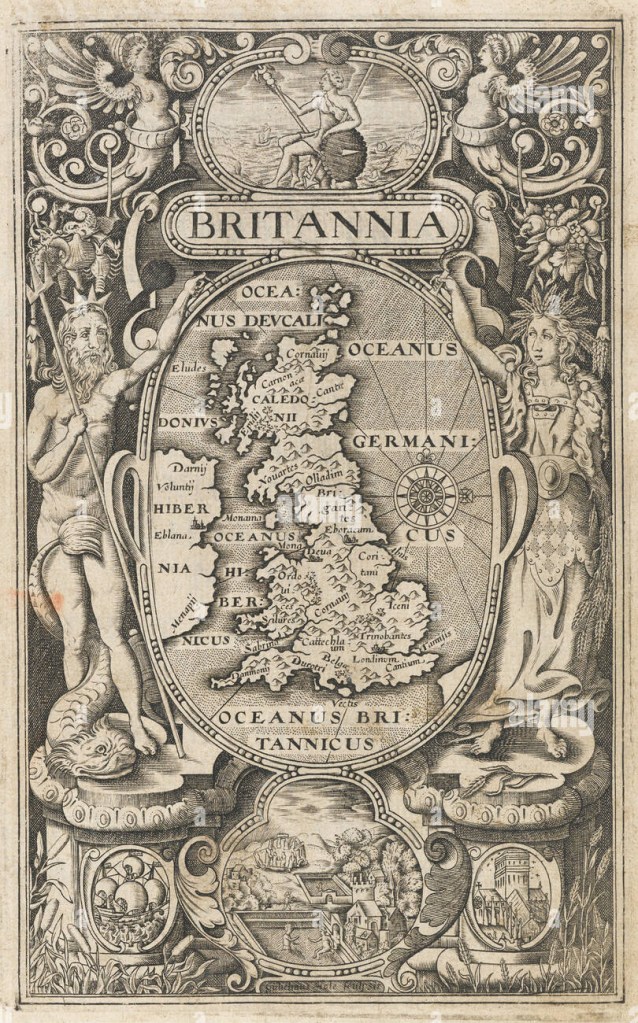

William Camden’s Brittania

“A map of England, Wales, Scotland eastern Ireland, in an oval supported by Neptune and Ceres, with vignettes of Britannia sitting on a rock, a ship, St Paul’s Cathedral, and Stonehenge and the Roman Baths. On the map London and York are marked, but most of the other names are tribes. This frontispiece was one of three maps engraved by William Rogers (c.1545-c.1604) for the 1600 edition of William Camden’s ‘Britannia’, the fifth edition of the work, yet the first to contain maps. It was not until 1607 that a full suite of county maps was included, alongside a larger version of this map, engraved by William Hole.”

Chorography designates “a regional map in Renaissance geographic texts and the artistic description of regions” viewed and experienced from within linking “regional events at the time of occurrence in pictorial representations.” (Olwig 2001 and Curry 2005 cited in Päivi Kymäläinen and Ari A. Lehtinen 2010: 252). Chorography or place‐writing forms an aspect of the tri‐partite structure belonging to a classical Geographic distinction between Topography, Chorography and Geography, Päivi kymäläinen and Ari A. Lehtinen (2010). Chorography, defined by the polymath Ptolemy in the Geographike Hyphegesis (c.149AD) takes region as its lens. This field-based approach and detailed descriptor of place qualitatively maps characteristics of the locale by examining the constituent parts of that place “to describe the smallest details of places.” Morra J, Smith M (2006: 17-18). Cormack states “Chorography was the most wide ranging of the geographical subdisciplines, since it included an interest in genealogy, chronology, and antiquities, as well as local history and topography…unit[ing] an anecdotal interest in local families and […] genealogical and chronological research.” (Cormack 1991 cited in Rohl 2011: 22).

Chorography was re-discovered in Renaissance Geography and British Antiquarianism 16th -17th centuries. Historically William Camden’s Brittania (1586) or a Chorographicall Description of the most flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland is an encyclopaedic approach to a geographic, historical topographical survey of the British Isles which has been identified as a classic exemplar of the renaissance of a chorographic work “connecting past and present through the medium of space, land, region or country.” (Rohl 2011: 22). Camden’s place in this changing historiographical framework of the English Renaissance is critical to elevating the field of historical studies in tandem with scientific documentation as a new and original contribution to knowledge and the discovery of ‘England’ and a sense of ‘Englishness’ (Richardson 2204: 112).

With its overriding pre-occupation with place Camden’s Brittania (1586), arranged chronologically, is a county-by-county survey of England & Wales which travels from the South to the North and represents a new ‘topographical-historical method’ (Mendyk 1986 cited in Rohl 2011: 22). The science of map making was still in it’s infancy but Camden was linked to its development and utilised it when it became available (Richardson 2004:117). Cartographic representations however “aim at synchronic representation”, chorographic descriptions of the countryside, by contrast, opt instead for the diachronic.” Reconstructing a topographically organised historical account in a specific area. Hence in Marchitello’s formulation “Chorography is the typically narrative and only occasionally graphic practice of delineating topography not exclusively as it exists in the present moment, but as it has existed historically. This means not only describing surface features of the land (rivers, forests, etc.), but also the “place” a given locale has held in history, including the languages spoken there, the customs of it’s people, material artefacts the land may hold, and so forth.” Marchitello in (Swann 2001, p.101). British Antiquarianism therefore retrieved chorography and recreated it in an expanded field, re-interpreting its legacy, ensuring its survival, restoration and continuing communication. Susan Stewart discusses the antiquarian as being “moved by a nostalgia of origin and presence” whose “function is to validate the culture of ground.” (1984:153)

Text reproduced from https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=31158455803&cm_mmc=ggl--UK_Shopp_RareStandard--product_id=bi%3A%2031158455803-_-keyword=&gclid=CjwKCAiApvebBhAvEiwAe7mHSKrgSaHbIJ-gLMONnS4zfobOGGL_kNcSs86HQENjxVf97aIYKEEEchoCF4YQAvD_BwE (accessed23/11/22)

Micro Critique Paper No.3

Introduction: Analysis of the following articles have revealed problems in defining the field of chorography as well as methods, theories and insights which warrant further examination. These summaries identify, illuminate and reflect on these issues and their implications in theory and practice.

Paper 3: Rohl, Darrell J. (2012) Chorography: History, Theory and Potential for Archaeological Research. TRAC 2011: Proceedings of the Twenty-First Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference. pp. 19-32.

The aim of this paper is a ‘tentative’ attempt at a theoretical framework informed by a close reading of classical texts in relation to contemporary discourse. Rohl states prior translations of Ptolemy’s description of chorography have conflated it with ‘likeness’. Within chorography’s history the term did become synonymous with a regional map gathering “information in the form of pictorial representations” (Kymäläinen and Lehtinen 2010: 252). Although he does not acknowledge this alternate history Rohl states in the 19th–20th centuries chorography gave way to ‘empirical […] topographic and spatial analysis’ which we might understand as cartography in its present sense. According to Rohl this coincided with the sublimation of antiquarianism into the discipline of archaeology. He also notes the resurgence of chorography in historical, literary and archaeological discourse and the study of ‘early modern Britain’.

Rohl’s theoretical chorographic framework is built upon a variety of historic and contemporary sources which in practice would be difficult to quantify. Within this Rohl cites Bossing who places the existentially emplaced literature or geopoetics of Thoreau into the tradition (1999) whose emphasis on chorography as place-writing is a literal translation of the term. Bossing’s quote concerning chorography’s textual ‘advantage over cartography’ appears misplaced since the term cartography is not synonymous with chorography. Again there is an overt emphasis on representation creating a simple binary which appears unproductive. Subordinating the visual to the textual or vice versa indicates on ongoing argument between mimesis and diegesis. However, some antiquarian works and chorographic maps are iconotextual. Rohl’s way out of this aporia is to expand his use of the term representation into ‘multi-media’ (actually employed by McLucas, see below) noting the unproductive limitation of chorography to ‘writing.’ However, this is a rather limited interpretation of the suffix graphy which is a combinatory form denoting a process or form of drawing, writing, representing, recording, describing and therefore is not limited to writing.

In both practices it is worth noting the intersection of region or place, event and temporality. There is a significant corpus on the chorographic map however I maintain the archaeological trajectory for this research will enable an expanded application of chorographic methodology to artistic practice. Rohl discusses these investigations which have been driven by Michael Shanks and his collaborations with Mike Pearson and the late Clifford McLucas, visual theorist. Pearson and McLucas co-founded the Welsh site specific-theatre company Brith Gof (National Library of Wales 2013). “Brith Gof was part of a distinct and European tradition in the contemporary performing arts – visual, physical, amplified, poetic and highly designed. Rather than focusing on the dramatic script, its work is part of an ecology of ideas, aesthetics and practices which foregrounds the location of performance, the physical body of the performer, and relationships with audience and constituency. Brith Gof’s works thus deal with issues such as the nature of place and its relation with identity, and the presence of the past in strategies of cultural resistance and community construction.” [1] Their site specific multi media works dealt with memory, place and belonging.

Pearson and Shanks employed a metaphor for antiquarian approaches; the Deep Map, a term appropriated from Heat-Moon, PrairyErth (a deep map) (1991). This work is a literary cartography of place, an epic tome and a 9 year sojourn across a single Kansas County recording all manner of incidences and is described by Calder as a form of “vertical travel writing” that interweaves “autobiography, archaeology, stories, memories, folklore, traces, reportage, weather, interviews, natural history, science, and intuition”. [2] According to Shanks the deep map ‘attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place’ (Pearson and Shanks 2001:64). McLucas outlines a ten-point scale of the Deep Map: No.4 states ’they will be genuinely multi-media’ (Jones and Urbanski n.d). Rohl does not discuss McLucas further. This deep map echoes the ‘thick description’ of ethnographic fieldwork which aims to ‘draw large conclusions from small but very densely textured facts.’ (Geertz 1973: 28). Pearson’s own exercise in deep mapping is a complex intertextual topography and autobiographical derivé incorporating region, locale, chorography, landscape, memory, archaeology and performance where historical, social, cultural and environmental temporalities are foregrounded. Landscape is not used here literally in reference to the scene of the action; Lincolnshire but as a symbolic and metaphorical re-imagining, through landscapes past and present.

Rohl more explicitly states the link between Landscape Archaeology and chorography owing to their focus on multi-temporal place relations. He expands on the list of the ten chorographic methods, explaining how they operate in relation to fieldwork, suggesting they are selectively practised according to the object of study. These include 1] “Regional Field Survey: This involves both the experience and the research of the choros and originates from chorography’s theoretical emphases on place and experiece. 2] Inquiry using a variety of sources i.e documents, maps, interviews, digital databases and GIS. 3] Collection of facts, stories and objects. 4] Detailed description and/or measurement – of specific sites, structures, people and objects encountered. 5] Listing of notable features, specific sites, artefacts and historical events. 6] Analysis examination of place names, sites, objects that is broadly representative. 7] Visualisation in the form of vivid textual description, drawings, phots, reconstructions, maps, performance and new media. 8] Historiography – examination and tracing of previous accounts, perspectives and interpretations. 9] Critical Thinking on all evidence collected and personal experiences. 10] Presentation and/or Publication – communication of results to experts or the broader public within and without the bounds of the choros.” pp.28-29 He maintains the importance of chorography in the development of archaeology in Britain. Rohl concludes with his PhD research, a chorographic account of the Antonine Wall in Scotland. He also urges those concerned with the histories and memories of place, landscape, monument and regions to devise and develop chorographic sensibilities.

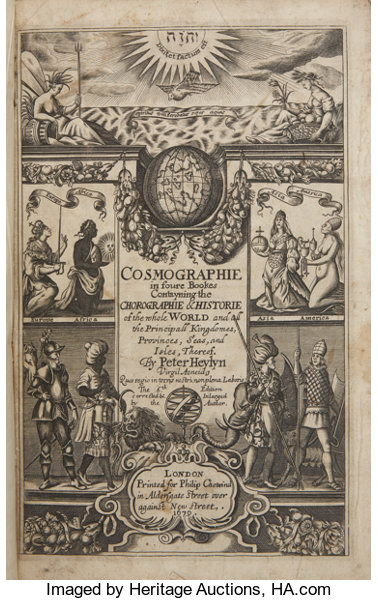

Image & text reproduced from https://historical.ha.com/itm/books/non-fiction/peter-heylyn-cosmography-in-four-books-containing-the-chorography-and-history-of-the-whole-world-and-all-the/a/6043-36218.s (accessed 03/11/22)

[1] https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/26.html (accessed 23/08/23)

[2] Calder. A, “The Wilderness Plot, the Deep Map, and Sharon Butala’s Changing Prairie.” Essays on Canadian Writing 77 (2002)pp. 164–70)