This PhD by practice explores chorography’s significance as a methodological tool in contemporary artistic practice, critically re-examining its historic yet neglected role in the documentation of place. Originating in Classical Geography (Ptolemy, c.149AD), chorography, or “place writing”, is historically understood as the detailed description and mapping of regions. This field-based approach qualitatively maps characteristics of the locale by examining its constituent parts. Historically, it has functioned as both a field-based method of qualitatively mapping and as an artistic or literary mode, linking events to landscape through pictorial and textual representation. Chorography was rediscovered in Renaissance Geography and British Antiquarianism in the 16th-17th centuries. Historically William Camden’s Brittania (1586) is an encyclopaedic approach to a geographic, “topographical-historical” (Mendyk, 1986, p.459) survey of the British Isles, which has been identified as a classic exemplar of the renaissance of a chorographic work “connecting past and present through the medium of space, land, region or country” (Rohl,2011, p.6). Britannia was part of an epic attempt to map the nation and give people a sense of cultural identity and belonging. British Antiquarianism retrieved chorography and recreated it in an expanded field of writing, reinterpreting its legacy, ensuring its survival, restoration, and continued communication.

While chorography has traditionally been seen as a representational tool, recent scholarship in cultural studies, archaeology, and performance has renewed interest in its methodological richness and interdisciplinary potential (Pearson, 2006; Shanks & Witmore, 2010; Rohl 2011, 2012, 2014). Yet there remains an absence of synthesis between these fields, and a lack of attention to gendered, embodied, and performative approaches, which this research addresses. Although chorography is pre-disciplinary, Shanks & Witmore (2010) claim that a genetic link underlies contemporary disciplinary approaches across heritage management, tourism, archaeology, historical geography, and contemporary art practice. They argue for a genealogical understanding of interdisciplinary practices concerned with relations of land, place, memory, and identity to understand present practical and academic positions. It is this link I am trying to follow and establish in contemporary artistic practice and research.

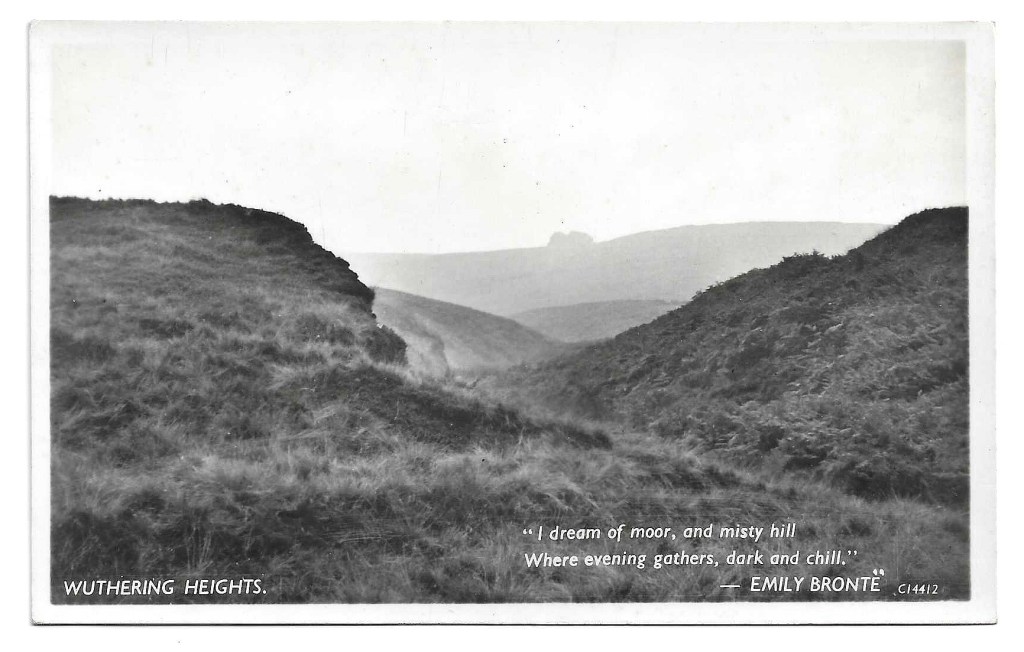

Central to this project is a critical re-examination of chorography in contemporary artistic practice, moving from documentation and representation to performance and embodiment. Drawing on Judith Butler’s theory of performativity (Butler, 1999), the research investigates how the body, particularly the gendered and mobile body, serves as a site of historical crossing, memory, and meaning-making. This shift has profound implications for who and what is remembered or forgotten, and for how places are re-collected and re-presented. Brontë Country, straddling West Yorkshire and the East Lancashire Pennines, has been chosen as the primary site for this investigation. Valued for its literary, historic, and symbolic significance, this landscape is both an active shaping presence (as in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, 1847) and a locus for contemporary artistic engagement. The region’s legacy of travel, narrative, fiction, gendered relations (a feature of their writing which is also lacking in chorographic history) and the literary imagination, compounded by the Brontës’ own use of pseudonyms, a strategy adopted in the practice research, renders it an exemplary terrain for rethinking chorography through a feminist, performative, and practice-led lens. This project approaches chorography not as a static or descriptive tradition, but as a speculative, embodied, and interdisciplinary methodology. Artistic practice, including moving image, performance writing, installation, and critical-creative text, serves both to enact and to interrogate chorographic methods: mapping not just physical terrain but also the complex intersections of place, history, narrative, cultural memory, gender, and the performative construction of identity. By combining historical method with contemporary form, the research aims to renew chorography’s relevance, to understand place not only artistically, but physically, contextually, and historically, and to open new possibilities for artistic research in and through place.