School of Design – Art and Design (practice-based) PhD 2023, Place-based and site responsive practice research

Aims and Objectives:

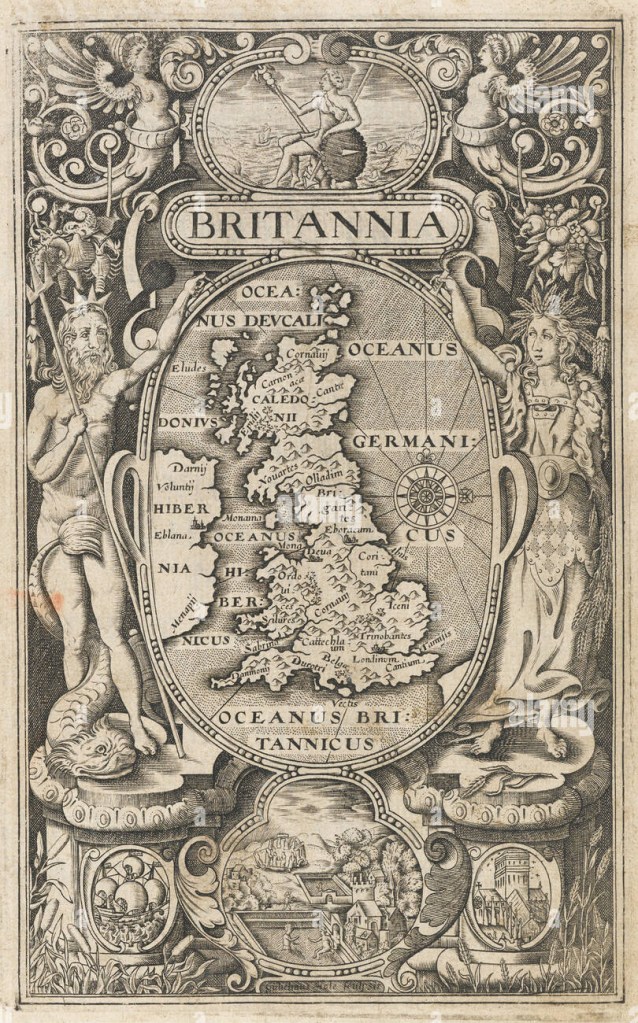

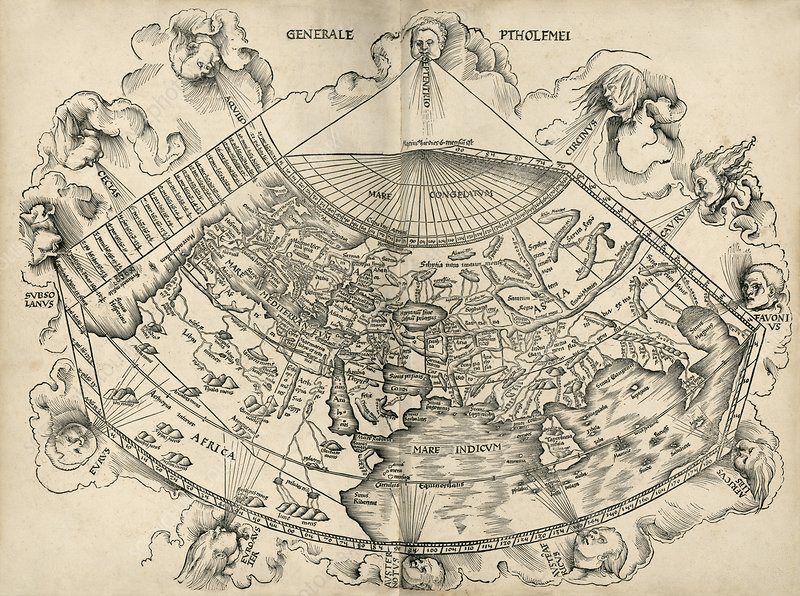

This PhD by practice aims to explore chorography’s relevance as an organising principle in contemporary artistic practice and critically address the historic yet neglected role of chorography in the documentation of place. Pertinent to research across diverse academic disciplines this proposal is timely, relevant, and contemporaneous. Chorography, or place writing, is the artistic representation of a regional map which originated in Classical Geography (c.149AD). This field-based approach and detailed descriptor of place takes region as its lens and qualitatively maps characteristics of the locale by examining the constituent parts of that place. If a sensory physical mapping of place occurs prior to representation where is the body in the process of chorography?. A particular focus of this research is to distinguish the performance of chorography from its documentation and re-presentation. Although a historic understanding is necessary this research recognises the body is itself a site of historical crossing that both transcends and incorporates these boundaries made possible by the very nature of its mobility, which has implications for who, what and how people and places are re-membered and re-presented. A critical reflection and practical exploration must recognise these relations do not occur in isolation but ‘in situ’ and within a context that affects how they are critically, ideologically, philosophically and historically situated.

Currently there is a renewed methodological interest and broadly conceived place relations in chorography within Cultural Studies, Archaeology and Performance. These forms of chorography, whilst practically and theoretically rooted in various strands of its developmental history, reflect its methodological richness and interdisciplinary nature although they do not have a locus as yet aligned. Therefore there is a need to analyse and synthesise these discrete bodies of knowledge that reflect current cultural pre-occupations with chorography to provide a clearer understanding of the relevance, meaning and impact of chorography today. I therefore propose the following outcomes:

- Critically evaluate and determine chorography’s relevance and its application as a methodological tool in contemporary artistic practice and research.

- Create new criteria to examine practices of place making by restoring, developing and communicating a connection between chorography past and present.

- Assess and synthesise discrete bodies of knowledge from diverse spheres of theory and practice that reflect current cultural pre-occupations and a renewed interest in chorography’s application and theorisation.

- Theorise chorography beyond its original conception, draw conclusions and propose future orientations, applications and developments

Relevance to Professional or Academic Field/Literature Review:

Selected practitioners and researchers of relevance to this study include Michael Shanks, Archaeologist, Stanford, Mike Pearson, formerly Performance Studies, Aberystwyth and visual theorist Clifford McLucas. Their work Theatre/Archaeology (2001) creates a porous space whereby archaeological and performance theory combine to provide an architecture for the event whose underlying questions was the representation of place and event and the role of landscape within it.Their concept of Deep Mapping (after William Heat Least-Moon) is derived from chorography.

This concept of the Deep Map echoes the concept of ‘thick description’ employed in ethnographic research (Geertz pace Ryle 1973). They are using the genre as a means to create techniques and re-think approaches to communities, locales and events. Their work incorporates chorography into performance and archaeology to activate, re-activate, question, examine and perform the histories of place utilising a range of methodological, archaeological, performance and narrative techniques including biography, memoir, folklore, topography to juxtapose and interpenetrate the historical and the contemporary.

Pearson’s exercise in deep mapping (2007) is a complex intertextual topography and biographical derivé incorporating region, locale, chorography, landscape, memory, archaeology and performance where historical, social, cultural and environmental temporalities are foregrounded. The scholarly work of Darrell J. Rohl, Archaeologist, Durham University, whose research is organised around past, present, people and place, identifies chorographic methods in archaeological fieldwork and interpretation (2012). Nicoletta Isar, Cultural Studies, Copenhagen University (2009) explores chorography and the performative relation between space and movement. This has largely been conceived under Dr A. Lidov’s neologism Hierotopy (2002), the organisation and mediation of sacred spaces, a transdisciplinary approach combining art history, archaeology and cultural anthropology. Poetic and philosophical connections can be traced in Kristeva (1984) and Derrida (1995).Prior research on this topic has been informed by geographer Inger Birkeland’s theory of chorography as an act of journeying, a socially narrated identity and material embodiment of place (2005).

How will your proposed research fit into the existing body of academic knowledge and practice in the professional field?

Shanks and Witmore (2010) identify common components of Antiquarianism in chorography including local and national history, geography, the regional, examination of archaeological remains and the act of collecting. Although chorography is pre-disciplinary they claim a genetic link forms the basis of contemporary disciplinary approaches across heritage management, tourism, archaeology, historical geography and contemporary arts practice. Although these claims are not substantiated they argue for a genealogical understanding of inter or trans-disciplinary practices concerned with relations of land, place, memory and locational identity to provide an enhanced understanding of present disciplinary, practical and academic positions. It is this link that I am trying to pick up and establish in contemporary artistic practice and research.

What are the expected outcomes for artistic practice and how does this contribute to the research?

Utilising chorography as an organising principle in artistic practice I aim to realise a historically grounded exploration of place by performing and documenting embodied, visual, textual and symbolic mappings through strategies such as image and text, narrative, the intimate and fact and fiction. These mappings will form the basis of artworks, critical and performance writing, book works, performance and installation which will translate chorographic methods and the physical act of mapping into artistic practice. As direct address to the questions posed theoretical concerns would be embedded in concrete action signifying an intention to fold the critical into the personal, the political into the poetic, the sensual into the discursive and the performative into the rhetorical. This research will create new criteria with which to examine and re-interpret contemporary practices of place making by retrieving, restoring, developing and recreating a connection between chorography past and present. Combining historic method with contemporaneous form will enable a renewed understanding of the chorography of place not just artistically but physically, contextually and historically.

How will your research enhance knowledge or contribute to new understandings of the subject?

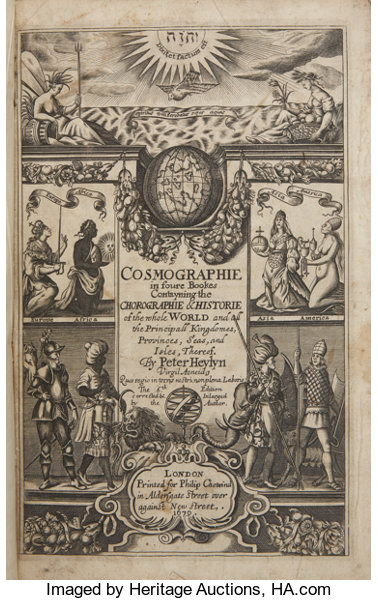

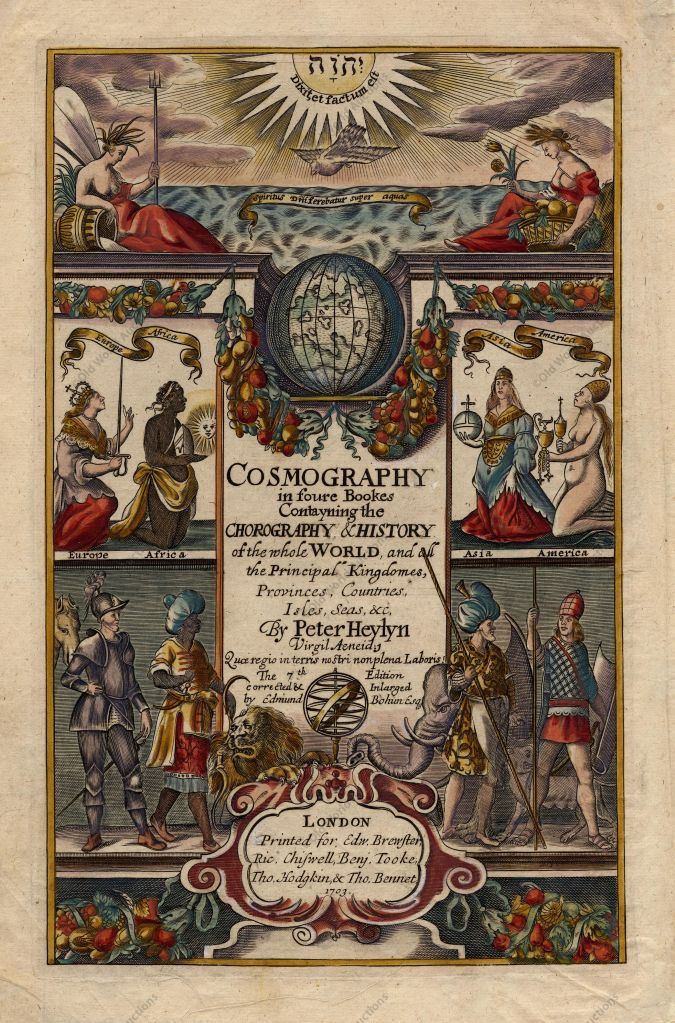

Prior studies framed within visual arts do not adequately recuperate the concept, and its pertinence to the theorisation, contextualisation and politicisation of performative embodied tactics and spatial practices ‘space is a practised place’ (De Certeau 1984), O’Sullivan, Jill (2011) The chorographic vision: an investigation into the historical and contemporary visual literacy of chorography, PhD thesis, James Cook University (AU). This study traces the history and symbolism of chorography as a visual literacy of place through cartography and the graphic medium of print, privileging the map as the primary visual signifier of chorography. Although the study does acknowledge other forms of chorographic practice its principle aim is to map the development of historical chorography and the philosophical discourse on place whereby the practice based iterations reproduce historic practice without providing new applications or forms. It is these other forms of chorographic practice that depart from its historical nature that provide what I perceive to be chorography’s as yet unexplored methodological richness in artistic research and the layering of these historical crossings that connect the cultural and socio-political to the personal.

I argue that if the relations posited within chorography are firstly empirical, experiential and emplaced it cannot be fully articulated by focussing on the cartographic. Put simply the medium is not the method. There is a need to distinguish this act from its documentation and re-presentation to provide new theories, forms and applications by addressing the political implications of the embodied in the act of representation. To provide a contemporaneous account the performative relations between the body, mapping and place; the mobile, embodied and situated are therefore central to a contemporary interpretation of chorography (Butler 2011).

I therefore propose the following research questions:

- How can we perform the relations between public memory and personal narratives of cultural identity and belonging through the medium of place?

- What is the significance of visual, textual, artefactual and embodied experiences of place in constructing and mediating personal narratives of cultural identity and belonging and how can we perform their retrieval, survival, communication and recreation?

- If a sensory physical mapping of place occurs prior to representation where is the body in the process of chorography and how do we address the political implications of the embodied in the act of representation?

- How is the subject situated rhetorically amongst the cultural, factual, historical details and how might the subject be figured as a marginal detail of another narrative?

- Can the concept of physical liminality be transposed into the field of aesthetics and if so how?

Research Approaches: What methods do you intend to use to deliver your aims & objectives?

Case Studies:

Providing the scope and context to explore an independent chorographic research practice sites chosen for their cultural, historic, national, symbolic and mythological significance include Brontë Country which straddles West Yorkshire and the East Lancashire Pennines. Located to the west of the Bradford- Leeds conurbation, Kirklees and Calderdale. this landscape in Wuthering Heights is a continual and active shaping presence. Other sites include the Devil’s Bridge and St. Michael’s Mount, Cornwall. Interest in these sites has developed out of prior practice.

The former located in Aberystwyth, Wales consists of 3 bridges built on top of each other, the first bridge is dated circa. 11th century forming part of a pilgrimage route associated with the Monks at the nearby Strata Florida Abbey. The nearby Hafod Estate is managed by the National Trust. The symbolic site of pilgrimage St. Michaels Mount shares a deep verisimilitude with Mont St. Michel, Normandy, France. This island has a complex identity as spiritual centre, military stronghold, harbour and home which is related in mythology to 3 other locations in the UK connected by a singular narrative arc. This site is also managed by the National Trust. Conceivably one of these identified case studies, or an aspect of, could occupy the entire duration of the PhD.

Methods:

Chorography is a field based qualitative research method with a range of techniques to capture, map and re-present place as currently utilised in archaeological fieldwork and interpretation. Prior research has revealed how this approach might be applied in artistic practice however it does not account for the body in the field. To address this I propose a form of Ethnography classified as Composition Studies, Critical Ethnography is a “research practice, primarily related to education, whose purpose is to use a dialogue about a cultural context to develop critical action” whilst considering “the ethics and politics of representation in that practice and reporting of that dialogue and resulting actions.” (Brook and Hogg quoted in Gilbert Brown S and Dobrin, Sidney I, 2004:4). In this instance Chorography is that context. I would seek to combine this with Cultural Mapping as cultural enquiry, a mode of inquiry and a methodological tool that makes visible the ways local stories, practices, relationships, memories, and rituals constitute places as meaningful locations.

Image reproduced from https://www.oldworldauctions.com/catalog/lot/110/6 (accessed 26/04/23)