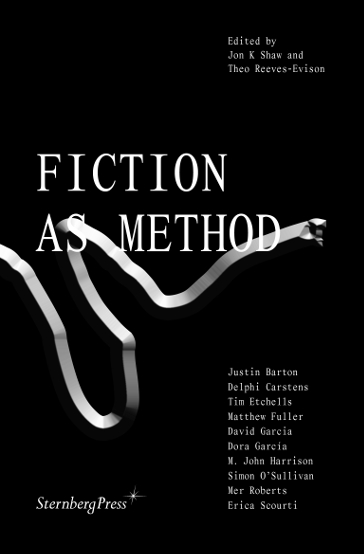

See the world through the eyes of a search engine, if only for a millisecond; throw the workings of power into sharper relief by any media necessary; reveal access points to other worlds within our own. In the anthology Fiction as Method, a mixture of new and established names in the fields of contemporary art, media theory, philosophy, and speculative fiction explore the diverse ways fiction manifests, and provide insights into subjects ranging from the hive mind of the art collective 0rphan Drift to the protocols of online self-presentation. With an extended introduction by the editors, the book invites reflection on how fictions proliferate, take on flesh, and are carried by a wide variety of mediums—including, but not limited to, the written word. In each case, fiction is bound up with the production and modulation of desire, the enfolding of matter and meaning, and the blending of practices that cast the existing world in a new light with those that participate in the creation of new openings of the possible.

Text and image reproduced from https://www.sternberg-press.com/product/fiction-as-method/ (accessed 23/10/25)