INTRODUCTION:

The purpose of this article is a comparative analysis of Drayton’s poems Ideas Mirrour and Poly-Olbion tracing echoes of the former in his latter richly chorographical work. For the purpose of this analysis the main focus is on Poly-Olbion as a prime exemplar of a chorographic work and I also aim to draw out strands that specifically follow the concept of the body as it pertains to one of my research questions: If a sensory physical mapping of place occurs prior to representation where is the body in the process of chorography and how do we address the political implications of the embodied in the act of representation? It appears this question is complex as bodies often appear symbolically in rich and intricate intertextual and iconotextual relationships. The body it seems emerges as a chimera hiding in plain sight like Poe’s purloined letter. A chorographic text such as Poly-Olbion offers tangible clues as to how this problematic might be addressed through practice.

POLY-OLBION (1612-1622):

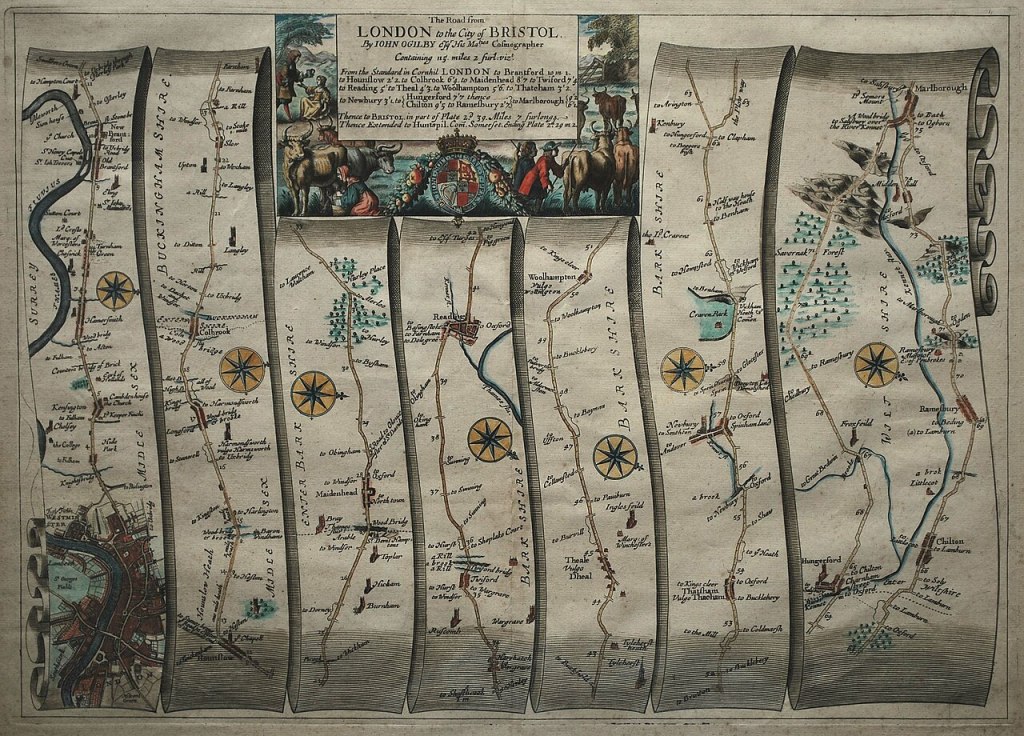

Poly-Olbion is an expansive poetic journey through the landscape, history, traditions and customs of early modern England and Wales. Originally published in two parts (1612, 1622), it is also a richly collaborative work: Michael Drayton’s 15,000-line poem navigates the nation county by county and is embellished by William Hole’s thirty engraved county maps. It is accompanied for its first eighteen ‘songs’ by John Selden’s prose illustrations. Drayton was a contemporary of Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, and Poly-Olbion crystallizes early modern ideas of nationalism, history and memory.

Drayton’s Early Sonnets, Poly-Olbion and Chorography:

Reyes outlines how Drayton’s epic Poly-Olbion was influenced and connected to his earlier sonnets particularly Ideas Mirrour (1594) later published as Idea (1599-1631) which both reflect and explore his interest in the history and topography of his country and celebrate ‘the discovery of England.’ p.1002The central trope in the allegorical Idea is fluvial and Drayton draws on ‘chorographic techniques to represent the beloved.’ p.1003 The central figure Idea, as an ideal representation of woman contained within the ideal geography of the English landscape, is embedded in the River Anker which runs through Drayton’s home county of Warwickshire and later appears in Poly-Olbion ‘where the poet finds the woman that he had originally praised under the poetic name of Idea.’p.1014

In Poly-Olbion Reyes identifies close connections to distant genres including sonnet, sequence, perspective, pastoral, epic, the heroic, lyrical and topographical as Poly-Olbion comes to represent the ‘eroticisation of the landscape’. whilst simultaneously trying to reify Drayton’s English identity. p.1003 Developments at the time facilitated this vision in the ‘revival of geographical writings and advancements in cartography’ and the renaissance of chorographic works in the 16th-17th Centuries, the most notable exemplar of the genre being William Camden’s Brittania (1586) pp.1003-4. Other proponents of the descriptive and primarily textual approach to history and travel narrative included the antiquarian works of John Leland’s Itinerary (1549) and William Lambarde’s A perambulation of Kent (1576). The rise of the ‘body politic’ and the ‘vision of the allegorical body’ supported ‘a spatial construction of national identity.’ p.1004 The rediscovery of Strabo and Ptolemy presupposed the encyclopedist approach to the genre but one whose methodologies ‘favoured a qualitative and localist point of view with a pictorial quality.’ P.1004

Reyes states that ‘Drayton’s interest in topography and the human body was driven by the Golden age of cosmography and cartography in England […] and reflected the idea of a human being as a microcosmos.’ p..1006 According to D K Smith (XXXX no date given) in the 16th-17th Centuries this ‘resulted in a new cartographical epistemology and a cartographic imagination that provided English authors with a new set of metaphors and rhetorical tropes related to space and it’s embodiment.’ P.1006 Reyes states ‘the conception of the body as space determined the aesthetics of Poly-Olbion’. She cites Traub (XXXX no date given) ‘the description of human figures became a common aesthetic in Renaissance cartographies – ‘maps began to imply that bodies may be a terrain to be charted and is responsible for the chorographic function of human figures.’ P.1006 The ‘representation of the human body came to be seen as a ‘conglomerate of delimited spaces’. P1006 According to Reyes this explains the ‘anthropomorphizing representations of rivers, hills, mountains and forests’ in the maps of Poly-Olbion and that this representation of space is commensurate with a topographical representation of the body. P.1006 Between Ideas Mirrour and Poly-Olbion there is a ‘reciprocal movement from the topographical representation of the human body and the personification of the landscape’. P.1006. This personification of the landscape is represented in the above engraving, the frontispiece to Poly-Olbion which Helgerson (XXXX no date given) states is ‘a goddess like woman dressed in a map’ holding the horn of plenty, which symbolizes prosperity, and who stands as ‘a living embodiment of nature.’ P.1010

Fig.1

Image reproduced from https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/trend-grown-up-colouring-been-11487014 (accessed 06/02/24)

Fig.2

https://fineartamerica.com/featured/poly-olbion-map-of-yorkshire-england-1622-michael-drayton.html (accessed 07/02/24)