Work in progress

“Ted Hughes (1930-1998) was born at 1 Aspinall Street, Mytholmroyd, in the West Riding of Yorkshire on the 17th August 1930. Ted was a pupil at the Burnley Road School until he was seven, when his family moved to Mexborough, in South Yorkshire. As a child he spent many hours exploring the countryside around Mytholmroyd, often in the company of his older brother, Gerald, and these experiences and the influences of the landscape were to inform much of his later poetry.

In ‘The Rock’, an autobiographical piece about his early childhood, Hughes writes about Scout Rock, whose cliff face provided ‘both the curtain and back-drop to existence‘. The area continued to be a powerful source of inspiration in his poetry long after he had left Yorkshire. Hughes described the experience of looking out of the skylight window of his bedroom on 1 Aspinall Street onto the Zion Chapel. The Chapel is long gone, but Zion Terrace remains, its name a reminder of more God-fearing times.

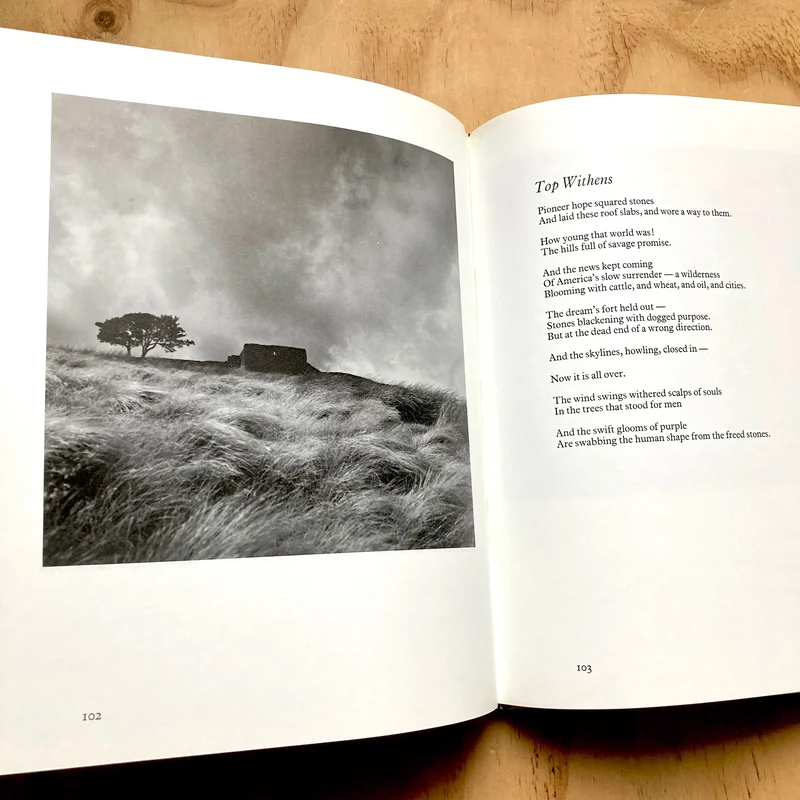

In his classic and richly personal collection Remains of Elmet: A Pennine Sequence (1979), with photographs by Fay Godwin, Hughes suggests that the Calder Valley was originally the kingdom of Elmet, the last Celtic land to fall to the Anglo-Saxons. A second, revised edition was published as Elmet in 1994.

Many of Hughes’s other poems also relate to the Calder Valley. ‘Six Young Men’, for example, was written at Hughes’s parents’ house at Heptonstall Slack in 1956. The poem describes a photograph belonging to Hughes’s father of six of his friends on an outing to Lumb Falls, taken just before the First World War.”

Text reproduced from https://www.theelmettrust.org/elmet-trust-ted-hughes/ (accessed 25/01/23). Images reproduced from Pinterest.

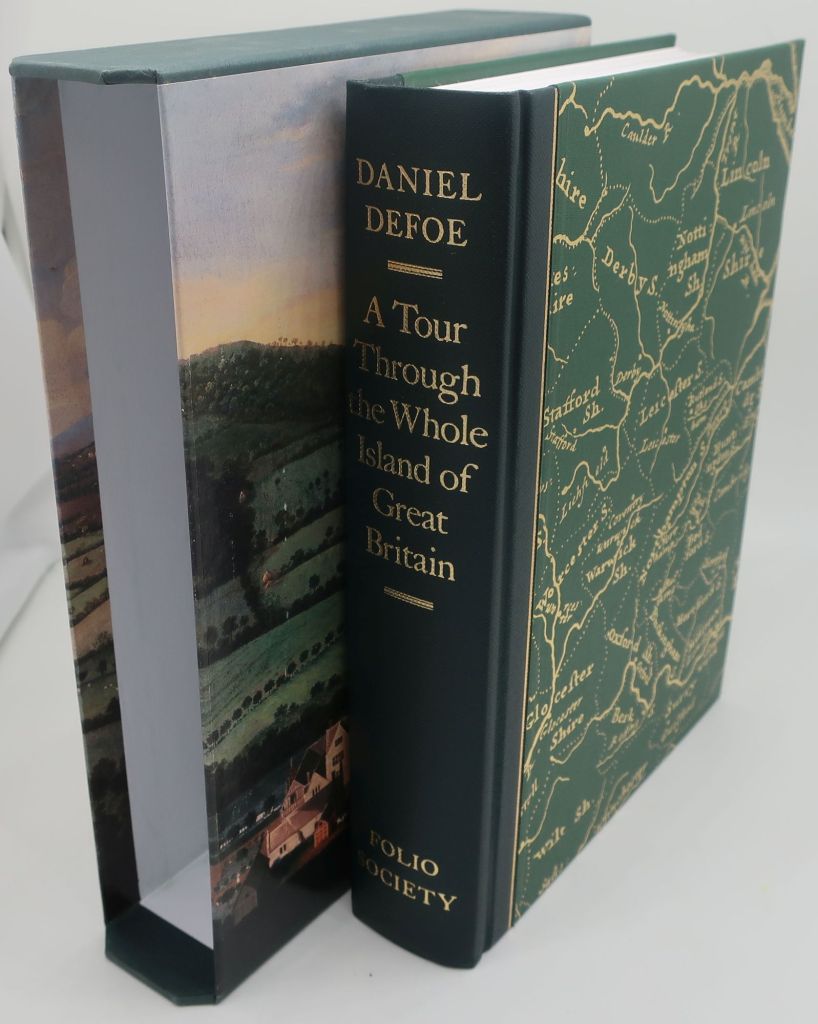

In the seventeenth century antiquarianism was a well-respected profession and antiquarian works were in demand, particularly amongst the gentry, who were especially interested in establishing lineage and the descent of land tenure. Although intended primarily as a source of information about who owned what and where, they often contained fascinating descriptions of the English landscape. Charles Lancaster has examined the town and county surveys of this period and selected the most interesting examples to illustrate the variety and richness of these depictions. Organised by region, he has provided detailed introductions to each excerpt. Including such writers as John Stow, William Dugdale, Elias Ashmole, Daniel Defoe, Gilbert White and Celia Fiennes, this is a book that will appeal to anyone with an interest in both national and local history and to lovers of English scenery.

Text reproduced from https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Seeing_England/6E87AwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 (accessed 14/01/24)

“Britain in the early eighteenth century: an introduction that is both informative and imaginative, reliable and entertaining. To the tradition of travel writing Daniel Defoe brings a lifetime’s experience as a businessman, soldier, economic journalist and spy, and his Tour (1724-6) is an invaluable source of social and economic history. But this book is far more than a beautifully written guide to Britain just before the industrial revolution, for Defoe possessed a wild, inventive streak that endows his work with astonishing energy and tension, and the Tour is his deeply imaginative response to a brave new economic world. By employing his skills as a chronicler, a polemicist and a creative writer keenly sensitive to the depredations of time, Defoe more than achieves his aim of rendering ‘the present state’ of Britain.”

Text reproduced from https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Tour_Through_the_Whole_Island_of_Great/b2MIlbEm6FYC?hl=en&gbpv=0 (accessed 05/01/24)