Introduction: Analysis of the following articles have revealed problems in defining the field of chorography as well as methods, theories and insights which warrant further examination. These summaries identify, illuminate and reflect on these issues and their implications in theory and practice.

Paper 3: Rohl, Darrell J. (2012) Chorography: History, Theory and Potential for Archaeological Research. TRAC 2011: Proceedings of the Twenty-First Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference. pp. 19-32.

The aim of this paper is a ‘tentative’ attempt at a theoretical framework informed by a close reading of classical texts in relation to contemporary discourse. Rohl states prior translations of Ptolemy’s description of chorography have conflated it with ‘likeness’. Within chorography’s history the term did become synonymous with a regional map gathering “information in the form of pictorial representations” (Kymäläinen and Lehtinen 2010: 252). Although he does not acknowledge this alternate history Rohl states in the 19th–20th centuries chorography gave way to ‘empirical […] topographic and spatial analysis’ which we might understand as cartography in its present sense. According to Rohl this coincided with the sublimation of antiquarianism into the discipline of archaeology. He also notes the resurgence of chorography in historical, literary and archaeological discourse and the study of ‘early modern Britain’.

Rohl’s theoretical chorographic framework is built upon a variety of historic and contemporary sources which in practice would be difficult to quantify. Within this Rohl cites Bossing who places the existentially emplaced literature or geopoetics of Thoreau into the tradition (1999) whose emphasis on chorography as place-writing is a literal translation of the term. Bossing’s quote concerning chorography’s textual ‘advantage over cartography’ appears misplaced since the term cartography is not synonymous with chorography. Again there is an overt emphasis on representation creating a simple binary which appears unproductive. Subordinating the visual to the textual or vice versa indicates on ongoing argument between mimesis and diegesis. However, some antiquarian works and chorographic maps are iconotextual. Rohl’s way out of this aporia is to expand his use of the term representation into ‘multi-media’ (actually employed by McLucas, see below) noting the unproductive limitation of chorography to ‘writing.’ However, this is a rather limited interpretation of the suffix graphy which is a combinatory form denoting a process or form of drawing, writing, representing, recording, describing and therefore is not limited to writing.

In both practices it is worth noting the intersection of region or place, event and temporality. There is a significant corpus on the chorographic map however I maintain the archaeological trajectory for this research will enable an expanded application of chorographic methodology to artistic practice. Rohl discusses these investigations which have been driven by Michael Shanks and his collaborations with Mike Pearson and the late Clifford McLucas, visual theorist. Pearson and McLucas co-founded the Welsh site specific-theatre company Brith Gof (National Library of Wales 2013). “Brith Gof was part of a distinct and European tradition in the contemporary performing arts – visual, physical, amplified, poetic and highly designed. Rather than focusing on the dramatic script, its work is part of an ecology of ideas, aesthetics and practices which foregrounds the location of performance, the physical body of the performer, and relationships with audience and constituency. Brith Gof’s works thus deal with issues such as the nature of place and its relation with identity, and the presence of the past in strategies of cultural resistance and community construction.” [1] Their site specific multi media works dealt with memory, place and belonging.

Pearson and Shanks employed a metaphor for antiquarian approaches; the Deep Map, a term appropriated from Heat-Moon, PrairyErth (a deep map) (1991). This work is a literary cartography of place, an epic tome and a 9 year sojourn across a single Kansas County recording all manner of incidences and is described by Calder as a form of “vertical travel writing” that interweaves “autobiography, archaeology, stories, memories, folklore, traces, reportage, weather, interviews, natural history, science, and intuition”. [2] According to Shanks the deep map ‘attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place’ (Pearson and Shanks 2001:64). McLucas outlines a ten-point scale of the Deep Map: No.4 states ’they will be genuinely multi-media’ (Jones and Urbanski n.d). Rohl does not discuss McLucas further. This deep map echoes the ‘thick description’ of ethnographic fieldwork which aims to ‘draw large conclusions from small but very densely textured facts.’ (Geertz 1973: 28). Pearson’s own exercise in deep mapping is a complex intertextual topography and autobiographical derivé incorporating region, locale, chorography, landscape, memory, archaeology and performance where historical, social, cultural and environmental temporalities are foregrounded. Landscape is not used here literally in reference to the scene of the action; Lincolnshire but as a symbolic and metaphorical re-imagining, through landscapes past and present.

Rohl more explicitly states the link between Landscape Archaeology and chorography owing to their focus on multi-temporal place relations. He expands on the list of the ten chorographic methods, explaining how they operate in relation to fieldwork, suggesting they are selectively practised according to the object of study. These include 1] “Regional Field Survey: This involves both the experience and the research of the choros and originates from chorography’s theoretical emphases on place and experiece. 2] Inquiry using a variety of sources i.e documents, maps, interviews, digital databases and GIS. 3] Collection of facts, stories and objects. 4] Detailed description and/or measurement – of specific sites, structures, people and objects encountered. 5] Listing of notable features, specific sites, artefacts and historical events. 6] Analysis examination of place names, sites, objects that is broadly representative. 7] Visualisation in the form of vivid textual description, drawings, phots, reconstructions, maps, performance and new media. 8] Historiography – examination and tracing of previous accounts, perspectives and interpretations. 9] Critical Thinking on all evidence collected and personal experiences. 10] Presentation and/or Publication – communication of results to experts or the broader public within and without the bounds of the choros.” pp.28-29 He maintains the importance of chorography in the development of archaeology in Britain. Rohl concludes with his PhD research, a chorographic account of the Antonine Wall in Scotland. He also urges those concerned with the histories and memories of place, landscape, monument and regions to devise and develop chorographic sensibilities.

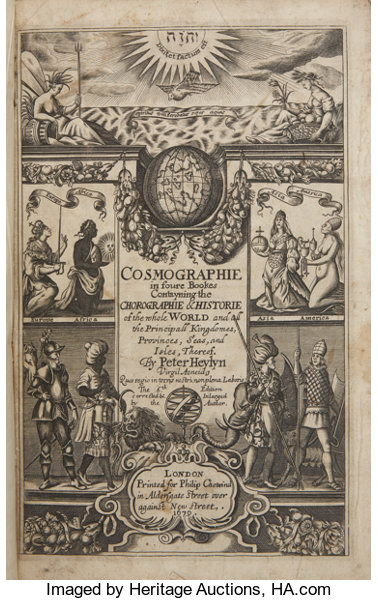

Image & text reproduced from https://historical.ha.com/itm/books/non-fiction/peter-heylyn-cosmography-in-four-books-containing-the-chorography-and-history-of-the-whole-world-and-all-the/a/6043-36218.s (accessed 03/11/22)

[1] https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/26.html (accessed 23/08/23)

[2] Calder. A, “The Wilderness Plot, the Deep Map, and Sharon Butala’s Changing Prairie.” Essays on Canadian Writing 77 (2002)pp. 164–70)