Introduction: Analysis of the following articles have revealed problems in defining the field of chorography as well as methods, theories and insights which warrant further examination. These summaries identify, illuminate and reflect on these issues and their implications in theory and practice.

Paper 4: Curry, M. (2005) “Toward A Geography of a World Without Maps: Lessons From Ptolemy And Postal Codes”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers [online] 95 (3), 680-691. Available from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00481.x/abstract [5th October 2015]

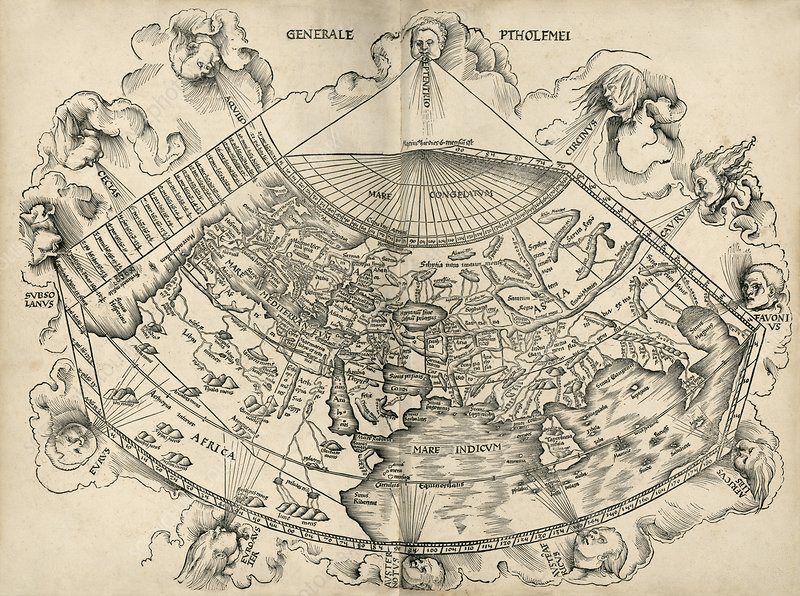

Curry’s paper is concerned with the conflation of place and space in contemporary discourse which commonly obfuscate and erase their differences. His primary aim is to elaborate upon the terms chorography, topography and geography and delineate their differences by examining their ‘technologies and practices’. He suggests chorography is limited to the geographer’s knowledge, clearly in the context of this research this is not the case and in his own words ‘it is alive and well.’ Curry argues these geographic ways of knowing each have their own objects of study; region, place and the earth’s surface. He is critical of both their neglect in discussions of place or analyses which focus on scale in relation to these concepts as opposed to form and function. Curry employs a complex analogy of the invention of the US ZIP code to illuminate his argument.

Curry compares and contrasts these terms by tracing and re-interpreting their origins to distinguish them from contemporary understandings. He locates chorography and topography within foundational concepts of place and memory. Chorography was a qualitative way of interpreting the world, both celestial and terrestrial, and this knowledge was located in ‘signs or symbols’ which aimed to perceive relations ‘between events, places and the times of their occurrence’. He relocates topography’s association with mapping by placing it in the oral tradition and the ‘art of memory’. In this context places are created, narrated, performed and re-formed through symbolic associations. Place and experience are coextensive with each other and this element of the mnemonic has already been established independently in prior research.

For Curry the importance of this argument is not simply a matter of different scales of apprehension, but more significantly is intrinsically linked to repositories of knowledge, dissemination and retrieval. He argues space was ‘invented’ against the backdrop of place, due to emergent technologies necessitated by an increase in information, leading to an erasure of the chorographic and topographic by the geographic. Chorography and topography represent human patterns of knowing and belonging in contrast to the panoptic vision of geography. The implications of this observation equate to an erasure of memory practices and a movement from an embodied and emplaced performance of knowledge to its commodification. Places are increasingly mediated by technology and this also applies to the digital records of archaeological fieldwork. For instance when I was introduced to archaeological fieldwork at Erddig, Wales the corresponding planar database managed by the Historic Buildings, Sites and Monuments Record comprises 24 topographic views of each location in the field; a complex palimpsest inconceivable in a single view. This centralization of information which allows for the preservation of heritage data becomes an abstracted space of typology and categorization devoid of the people that inhabited them or the places that created them.

Curry’s analogy of the standardisation of the ZIP code can, in the context of this paper, be equated with geography reaching its empirical, scientific, mathematical and spatial exactitude in the art of cartography. This organisation of geographical knowledge, in the case of the ZIP code, privileges spatial points and co-ordinates whereby the particularities of place, regions, difference, the local and thus topography and chorography are subsumed and erased by spatial systematisation, the realm of demographics and the global organisation of information.

Image reproduced from https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/428654/view/ptolemy-s-world-map-16th-century (accessed 03/11/22)