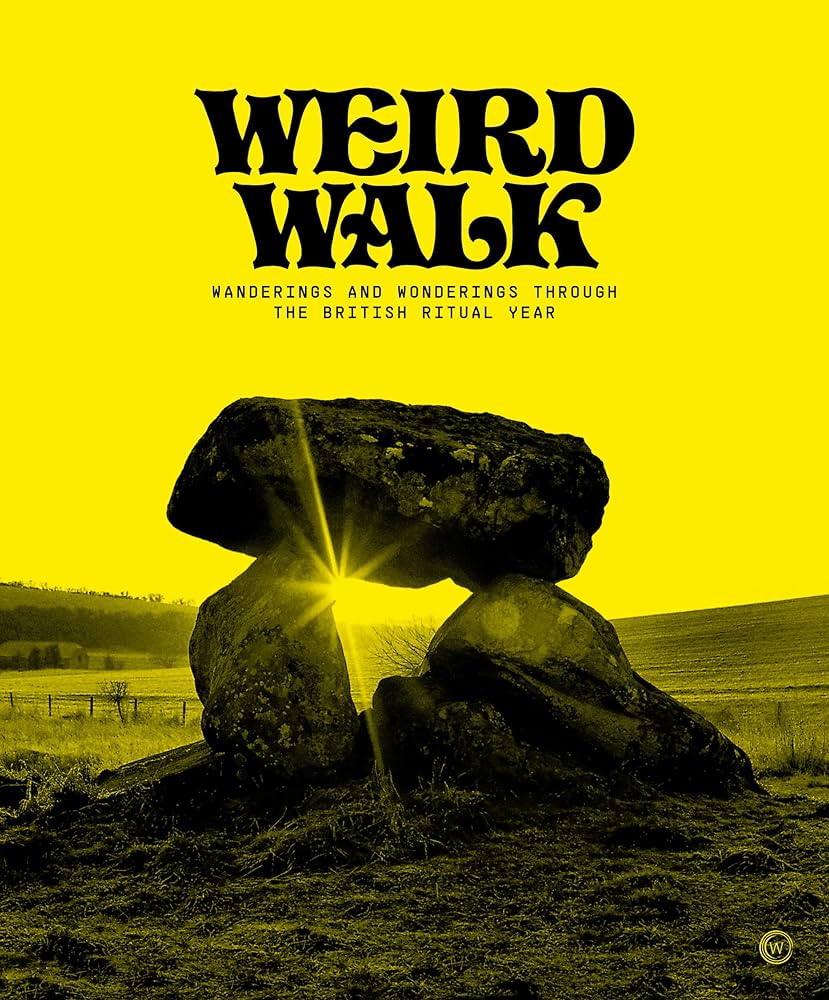

By walking the ancient landscape of Britain and following the wheel of the year, we can reconnect to our shared folklore, to the seasons and to nature. Let this hauntological gazetteer guide you through our enchanted places and strange seasonal rituals. SPRING- Watch the equinox sunrise light up the floating capstone of Pentre Ifan and connect with the Cailleach at the shrine of Tigh nam Bodach in the remote Highlands. SUMMER- Feel the resonance of ancient raves and rituals in the stone circles of southwest England’s Stanton Drew, Avebury and the Hurlers. AUTUMN- Bring in the harvest with the old gods at Coldrum Long Barrow, and brave the ghosts on misty Blakeney Point. WINTER- Make merry at the Chepstow wassail, and listen out for the sunken church bells of the lost medieval city of Dunwich. The first book by iconic zine creators and cultural phenomenon Weird Walk. This is a superbly designed guide to Britain’s strange and ancient places, to standing stones and pagan rituals, and to the process of re-enchantment via weird walking.

Text reproduced from https://www.weirdwalk.co.uk/ (accessed 04/03/24)