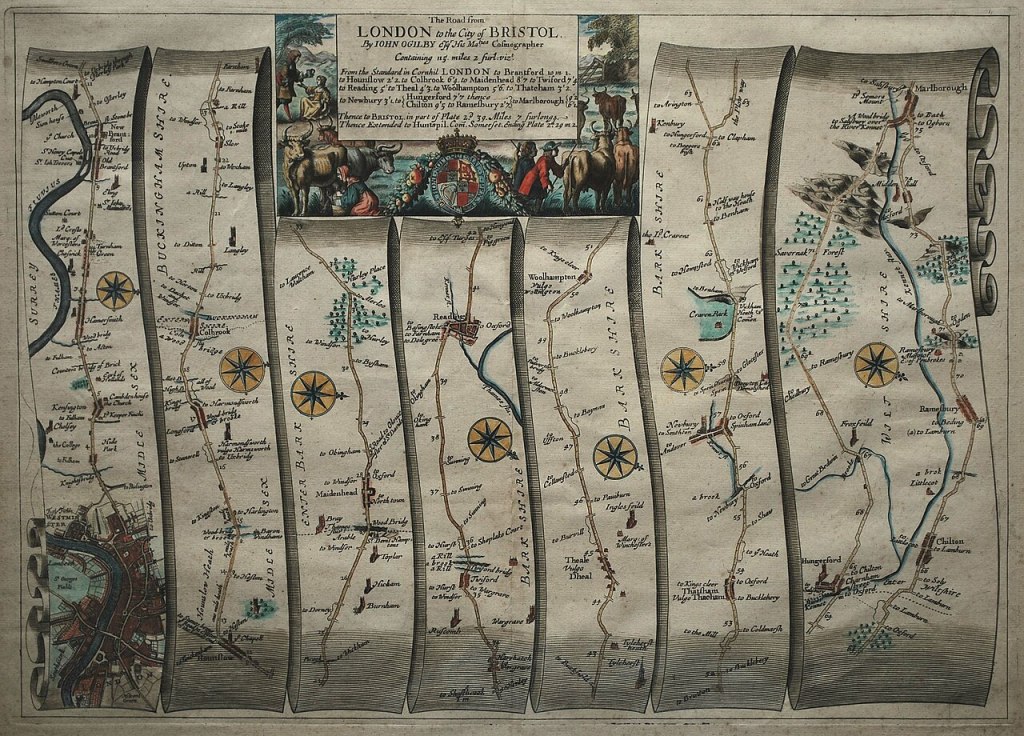

“John Ogilby, was born in Scotland in 1600, and held many different careers in his life; a dancing-master, theater owner, poet, translator, publisher and cartographer. He is most remembered for bringing English cartography into the scientific age with his 1675 road atlas of England and Wales titled, Britannia. To create the wonderfully detailed strip maps that displayed the topographical features and distances of the roads, Ogilby’s team of surveyors worked with the precise and easy-to-use perambulator or measuring wheel to record the distance of the roads in miles; implementing the standardized measurement of 1,760 yards per mile as defined by a 1592 Act of Parliament. They also used the surveyor’s compass or theodolite to better record the changes in the directions of the roads. Besides the use of scientific instruments, Britannia was also the first published work to use the scale of one inch equaling one mile, which became the prevailing scale for cartography. Through the use of detailed illustrations and precise technology, Ogilby’s Britannia became the first comprehensive and accurate road atlas for England and Wales, making it the prototype for almost all English road books published in the following century.”

1st image and text reproduced from https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/ogilbys-britannia-bringing-english-cartography-into-the-scientific-age/ (accessed 10/03/24). Map https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:John_Ogilby_%281675%29_Britannia_Atlas#/media/File:John_Ogilby_-_The_Road_from_London_to_the_City_of_Bristol_(1675).jpg (accessed 10/03/24)